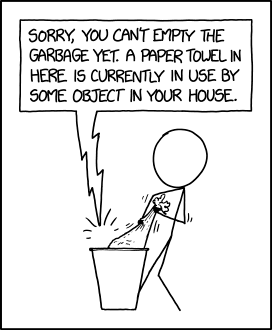

Garbage Collection (More Like Recycling)

How Your Runtime Reclaims and Reuses Memory Behind Your Back

Image Source: XKCD

Introduction

When we write code, we create data (values and objects), and that data must be stored somewhere. Most of the time, that “somewhere” is memory managed by the operating system and the language runtime. You can think of it as a big address space where your program stores the bits that make up objects: numbers, strings, arrays, structs, class instances, and so on.

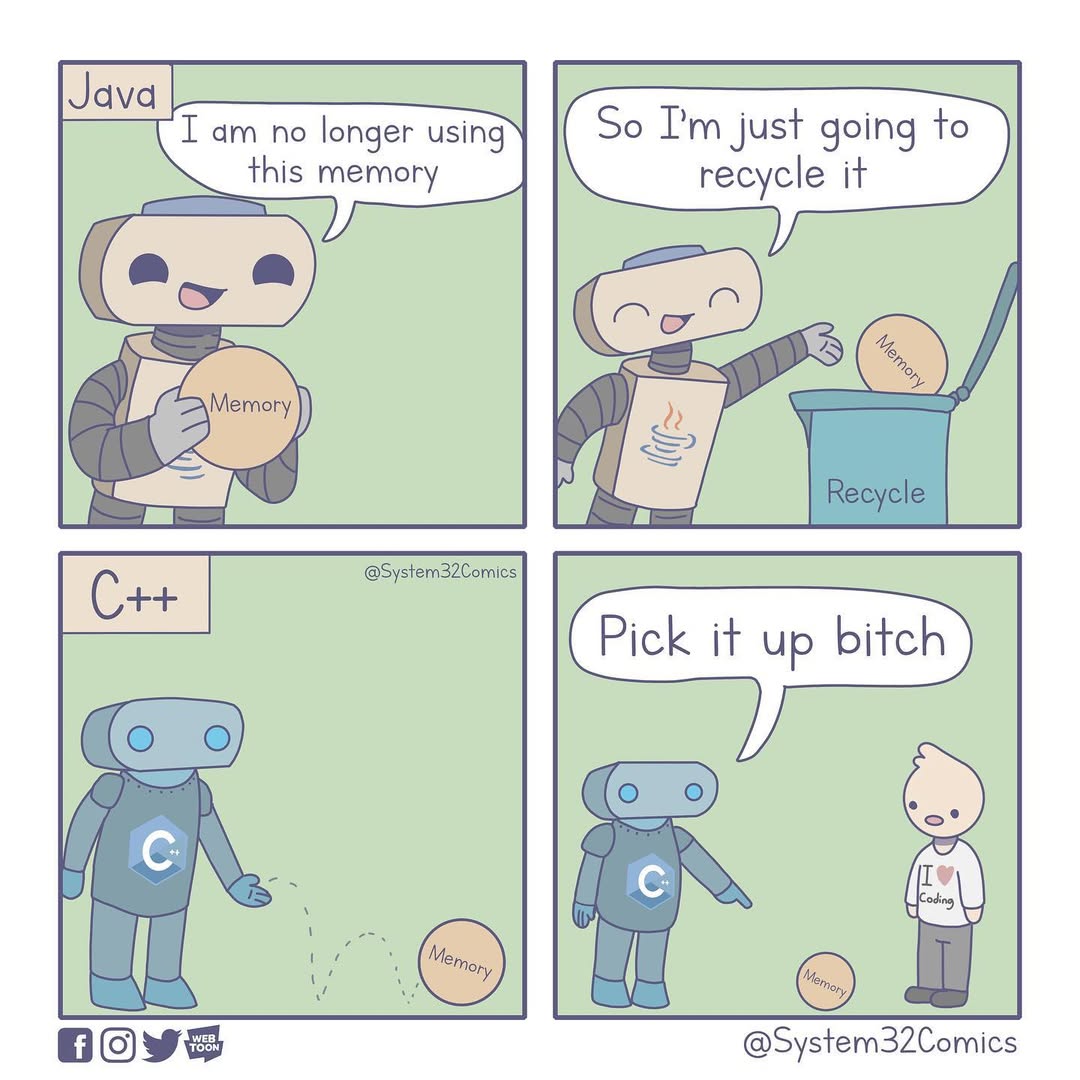

In some (typically lower-level) languages, creating an object often means explicitly allocating memory for it. You have to know how much you need, avoid writing past the space you were given, and, crucially, remember to free that memory when you’re done. If you don’t, the program may continue to accumulate unused allocations, resulting in a memory leak. If you free the wrong thing (or use memory after it’s been freed), you can get nastier failures — crashes, corrupted data, security vulnerabilities, the whole mess. (If you want examples of how memory bugs can spiral into real-world issues, here are recent write-ups involving vulnerabilities in MongoDB: MongoDB Unauthenticated Attacker Sensitive Memory Leak, Merry Christmas Day! Have a MongoDB security incident.)

Image Source: system32comics (Pardon the NSFW reference)

Keeping track of every allocation in a complex program is tedious and error-prone, which is exactly why many modern languages introduced garbage collection. In garbage-collected languages, you allocate memory freely, and the runtime periodically identifies memory that’s no longer reachable by your program and reclaims it for reuse.

That sounds like “taking out the trash.” However, it’s often closer to recycling: identifying what’s still in use, separating it from what isn’t, and reorganizing memory so new objects can be allocated efficiently. In this article, we’ll demystify how garbage collection actually works and perhaps, why “memory recycling” might be the more honest name. We’re going to peek under the hood (or into the bin) and see what’s really going on.

The Heap (of Garbage?)

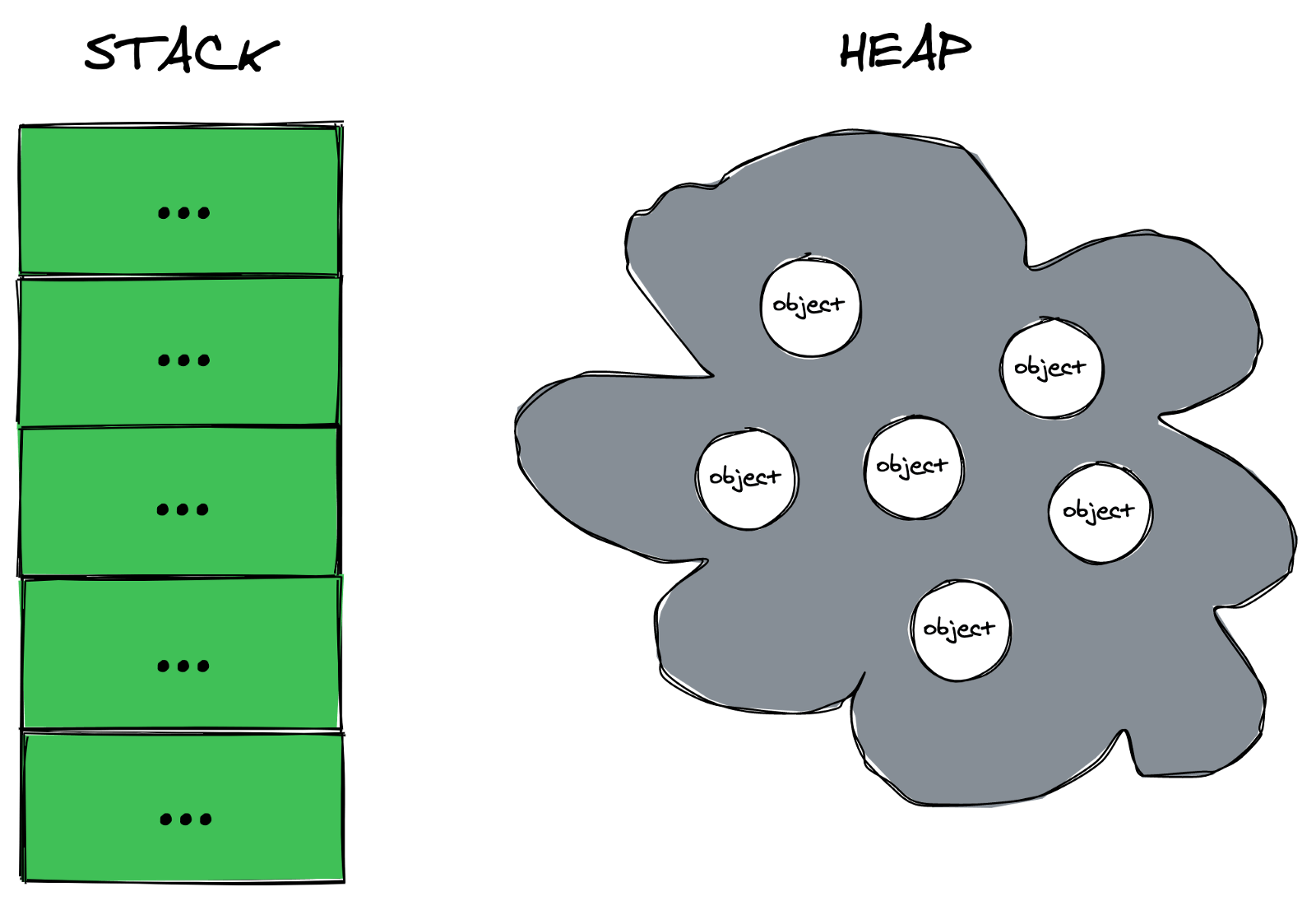

Before we get into how garbage collection works, it’s helpful to know where it works. Most programs use two main regions of memory, the stack and the heap.

The stack is like a fast, automatic workspace your program uses for things like function calls and local variables. Every time a function runs, it gets a stack frame; when the function returns, that frame is popped off. Memory on the stack is reclaimed immediately and predictably, so it doesn’t need any special cleanup. Stack allocation is “automatic” in the literal sense: entry into and exit from a function determine the lifetime of the memory used by that function call.

Image Source: Fundamentals of Garbage Collection

The heap, on the other hand, is a shared pool of memory used for data that needs to live beyond a single function call, or whose size/lifetime is hard to predict in advance (think objects, strings, arrays, dynamic data structures, and so on). You can allocate heap objects and keep them around by passing references across functions, storing them in other objects, or placing them in long-lived structures.

And that flexibility is exactly why the heap needs help. Heap allocations don’t have an obvious “end of life” the way stack frames do. In languages without a garbage collector, the programmer is responsible for returning heap memory when it’s no longer needed. In garbage-collected languages, the runtime takes on that job by periodically scanning the heap, figuring out what is still reachable, and reclaiming space from objects that aren’t.

What is Garbage?

It is the runtime’s job to determine which heap objects are still in use and which can be reclaimed. But how does it make the distinction? It can’t read the programmer’s intent, so it doesn’t know what they plan to do with an object. What it can do is check whether the program can still reach an object. If an object is still reachable by the running program, it’s alive. If it’s unreachable, it’s garbage and can be cleaned up (or the space reclaimed for use by a different object).

We can think of the program’s memory as a graph:

- Objects are nodes (strings, arrays, class instances, etc.)

- References/pointers are edges between nodes

If you can start from a known “entry point” and follow references to an object, then the program could still access it. That object must be kept.

If there’s no path to an object, then no code can ever get to it again. It might as well not exist, so the runtime is free to reclaim its memory.

The Roots: Where Tracking Begins

Garbage collectors start from a small set of “definitely alive” references called roots. The exact types of roots vary by language and runtime, but typically include:

- Local variables on thread stacks (things currently in scope)

- Global or static variables

- CPU registers

- References held by the runtime itself (e.g., JIT/compiler metadata)

You can think of roots as places the program can directly “grab” data from at any moment.

Tracing the object graph

Image Source: Introduction to Garbage Collection - Grinnell College

From the roots, the GC traces outward:

- Look at every root reference.

- Mark the object it points to as alive.

- Follow that object’s references to other objects.

- Repeat until there’s nothing new to visit.

At the end of this traversal, the GC has effectively partitioned the heap into two sets:

- Reachable (alive): the program can still get to these objects.

- Unreachable (garbage): nothing points to them anymore, so the memory they occupy can be reclaimed.

A tiny example

Imagine this situation:

- A root points to object

X Xpoints toYYpoints toZ

So the GC can reach X -> Y -> Z, and all three are alive.

Now, suppose the code drops the last reference to X (e.g., a function returns or a variable is overwritten). If X is no longer reachable from any root, then Y and Z become unreachable too, even if they still point to each other.

The garbage collector doesn’t care whether objects reference each other. It only cares whether the program can reach them from the roots. This also enables tracing to handle cycles naturally. Two objects can be locked in an eternal embrace (like the Lovers of Valdarao), but if nothing reachable points to them, the GC can still collect them.

Now that we know what garbage is, let’s look at the different strategies runtimes use to find and collect it.

Strategies for Garbage Collection

There are multiple ways to take out the trash (or run a recycling program). Over the decades, language designers have developed several strategies for finding and reclaiming unreachable objects, and many real-world runtimes use hybrid approaches. Below are some of the most common methods.

Reference Counting: Keeping a Tally

In this method, each object maintains a counter of the number of references pointing to it.

- When we create a new reference to an object, its count goes up.

- When a reference goes away (a variable is overwritten, a scope ends), the count goes down.

- When the count hits zero, the object is immediately collectible, because nothing can reach it anymore.

For instance:

x -> [A] (refCount = 1)

x = null

[A] (refCount = 0) -> reclaim A

The appeal is simplicity and immediacy: objects are cleaned up the moment they are no longer in use, with no need to pause the program for a large collection phase. Languages like Python and PHP use reference counting at the core of their memory management.

The tradeoff here is circular references. If object A points to B and B points back to A, both counters stay at 1 even if nothing else in the program can reach either of them. The memory “leaks” unless the runtime has a secondary mechanism (like Python’s cycle detector) to catch these cases.

There’s also overhead to consider. Every assignment, every function call, and every time a reference is copied or dropped, the runtime must update the counter. In reference-heavy code, the bookkeeping can add up.

Mark-and-Sweep (Tracing GC)

Image Source: M17, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Mark-and-sweep takes the reachability approach we described in the previous section and turns it into a two-phase algorithm.

-

Mark phase: Starting from the roots, the GC traverses the object graph and marks every reachable object as alive.

-

Sweep phase: The GC walks through the entire heap. Any object that wasn’t marked is unreachable, so its memory is reclaimed. Marked objects then have their marks cleared in preparation for the next cycle.

Root -> A -> B

Heap: [A] [B] [C] [D]

Mark: keep keep - -

Sweep: reclaim C and D

The big advantage over reference counting is that mark-and-sweep handles cycles naturally, because it only cares whether an object is reachable from a root.

The tradeoff is that a full tracing pass can be disruptive. In a basic mark-and-sweep implementation, the program often pauses while the GC traces and sweeps the heap. The larger the heap, the more work there is to do, and the more noticeable the pause. Modern collectors mitigate this with incremental and concurrent techniques that do more of the work alongside the running program, but the fundamental tension between thoroughness and responsiveness remains.

Generational Collection: Most Objects Die Young

Generational collection is built on an empirical observation—the generational hypothesis: most objects have very short lifetimes. A temporary string built during a function call, an iterator, an intermediate calculation… these objects are created, used briefly, and become garbage almost immediately. A smaller fraction of objects (configuration, caches, long-lived data structures) stick around much longer.

Generational collectors exploit this by dividing the heap into regions, typically called generations:

- Young generation (nursery): Where new objects are allocated. This region is collected frequently because most of its contents are expected to die quickly. Since the region is small, these collections are fast.

- Old generation (tenured): Objects that survive one or more young generation collections get promoted here. This region is larger and is collected less often, since its objects have already proven likely to persist.

New objects -> Young (collected often) -> survivors -> Old (collected rarely)

Image Source: The CS 6120 Course Blog - Cornell University

The tradeoff is that we must track cross-generational references. If an old object points to a young object, the GC must not accidentally collect the young one during a “young-only” collection. So the runtime does bookkeeping (often via a write barrier and a remembered set) to remember “old → young” pointers. That tracking adds overhead, but it’s usually worth it because it avoids frequent scanning of the entire heap.

Many production collectors use some form of generational collection (often combined with concurrent or incremental techniques to reduce pause times). Examples include the JVM’s generational collectors, .NET’s GC, and JavaScript engines like V8.

Real-world collectors rarely use a single strategy in isolation. Modern GCs mix and match: copying and compacting collectors relocate surviving objects to reduce fragmentation; incremental and concurrent collectors interleave GC work with program execution to reduce pause times; and region-based collectors (like Java’s G1) divide the heap into independently collectible chunks and prioritize the ones with the most garbage. Some runtimes also try to avoid GC work entirely when possible via escape analysis; they prove that certain objects don’t outlive a function and allocate them on the stack instead, so the collector never has to touch them.

At the far end of the spectrum is the “no GC at runtime” approach: languages like Rust enforce ownership rules at compile time and free memory deterministically, without a runtime collector. The takeaway is that garbage collection isn’t a single algorithm. It’s a toolbox, and most production runtimes are creative hybrids tuned for different tradeoffs.

The Cost of Recycling

Garbage collection saves the programmer from having to manage memory themselves, but it doesn’t make memory management free (even though we never have to call free()). It shifts the cost from the code to the runtime, and that cost can show up in a few ways.

Pause Times

This is the most visible cost. When the GC runs, it may need to pause your program—or at least slow it down. In a basic stop-the-world collector, everything freezes while the GC traces and sweeps. These pauses can range from microseconds to tens of milliseconds (and, in extreme cases, longer), depending on heap size, the number of live objects, and the collector’s design.

For a batch job or a CLI tool, you might never notice. For a game rendering at 60 FPS, a multiplayer server, or a trading system, even a few milliseconds in the wrong place can be a real problem. This is why so much GC research focuses on reducing, hiding, or distributing pause times. Concurrent collectors, incremental passes, and region-based collection exist largely to address this.

Throughput Overhead

Even when the GC isn’t pausing your program, it’s still consuming resources. Tracing the object graph, maintaining write barriers for generational collectors, and copying or compacting live objects all consume CPU time that could otherwise be spent on your application logic. (And in runtimes that use reference counting/ARC, reference updates add overhead too.)

The overhead varies widely. A well-tuned collector might use only a small percentage of total CPU time. A poorly tuned one—or one dealing with a pathological allocation pattern—can eat significantly more. The general rule is that GC trades some raw throughput for the convenience (and safety) of not managing memory yourself.

Memory Overhead

Garbage collectors need headroom to work efficiently. If the heap is nearly full, the GC has to run more frequently, which increases pause times and CPU usage. Most collectors perform best when the heap has some breathing room, which means your program may use more memory than it strictly needs at any given moment.

Some strategies incur additional memory costs on top of this. Copying collectors need space to copy live objects into. Generational collectors maintain remembered sets to track cross-generational references. Reference counting adds metadata to track counts. None of these is enormous individually, but they add up, especially in memory-constrained environments, and especially when fragmentation forces the runtime to keep extra slack space around.

Unpredictability

Perhaps the subtlest cost is timing: you don’t control exactly when the GC runs, and you don’t control exactly how long it takes. You can influence it through tuning and allocation patterns, but ultimately, the runtime decides when to collect and how much work to do. That can make GC-related performance issues harder to reproduce, profile, and reason about than many other bottlenecks.

In manually managed languages, freeing memory is explicit and predictable: you pay the cost exactly where you wrote the free() call. With GC, that cost is deferred and amortized in ways that can be hard to connect back to the allocation behavior that triggered it.

So, is it worth it?

For most applications, yes—overwhelmingly. The bugs that manual memory management introduces (use-after-free, double-free, leaks) are often far more expensive in practice than the overhead a modern GC imposes. But “most applications” isn’t all applications, and understanding what you’re trading away helps you make informed decisions about when GC is the right fit and when you might want more control.

Conclusion: Better Than Recycling

We’ve been calling garbage collection a recycling program, and the metaphor holds up surprisingly well. The runtime traces what’s still reachable, separates it from what isn’t, and reclaims the leftovers so they can be put to work again.

But here’s where the metaphor breaks down—and in the best possible way. Real-world recycling degrades material. Paper loses fiber. Plastic weakens. Every cycle produces something a little worse than what came before. Reclaimed memory has no such problem. A freed byte is identical to a fresh one. There’s no wear, no downgrade, no loss of quality. The runtime hands it back in perfect condition, ready to become whatever your program needs next.

So the next time your program hums along without you writing a single malloc() or free(), take a moment to appreciate the quiet, efficient system working behind the scenes. It’s not just taking out the trash; it’s running a recycling program that never loses fidelity. And it’s doing it while you’re not looking.

Working on this blog post has been a lovely learning experience, and I thought it would be fun to write a small garbage collection library for C to harden the concepts. If you are interested in learning along, feel free to look at the repo and contribute. I put together a roadmap (with some help from Claude) and will walk through it and learn as we go. Find the repo here: garbagec.

References

- Incremental Garbage Collection in Ruby 2.2 — Heroku

- Baby’s First Garbage Collector — Bob Nystrom

- The Garbage Collection Handbook — gchandbook.org

- Boehm-Demers-Weiser GC — Hans Boehm

- Crafting Interpreters, Ch. 26: Garbage Collection — Bob Nystrom

- Writing a Simple Garbage Collector in C — Matt Plant- What different types of garbage collection are there? — Language Dev Stack Exchange

- Garbage Collection — Grinnell College CS302

- Fundamentals of Garbage Collection — Telerik

- Back to Basics: Generational Garbage Collection — Microsoft

- Java Garbage Collection Overview — Oracle

- Teaching Garbage Collection — Brown PLT

- Incremental GC — Heroku

- A Unified Theory of Garbage Collection — Cornell CS6120

- An Animated Guide to How Garbage Collection Algorithms Work — freeCodeCamp

- Memory Management Strategies: Garbage Collection, Reference Counting, and Beyond — Andrew Johnson

- Garbage Collection — Cornell CS4120

- Garbage Collection in Python — GeeksforGeeks

- Reference Counts — Python Docs (Extending Python)

- How does Python’s garbage collector detect circular references? — Stack Overflow

- Reference Counting — Python C API Docs

- Deep Understanding of Garbage Collection: Principles, Algorithms, and Optimization Strategies — threehappyer

- Generational Garbage Collection and Heap Memory — Incus Data

- Generational GC — Northwestern CS321

- MongoBleed Detector — Neo23x0 (GitHub)

- Fundamentals of Garbage Collection — Microsoft .NET Docs

- Introduction to Garbage Collection — dev.java

- Garbage Collection in Java — IBM

- How Does Garbage Collection Work in Java — Alibaba Tech

- Garbage Collection — ODU CS330

- Garbage Collection Algorithm: Mark-Sweep — Animesh Gaitonde

- Mark and Sweep Garbage Collection Algorithm — GeeksforGeeks

- Understanding Garbage Collection — Aerospike

- Understanding Garbage Collection — Naik

- Garbage Collection in Java — GeeksforGeeks