Linux Permissions

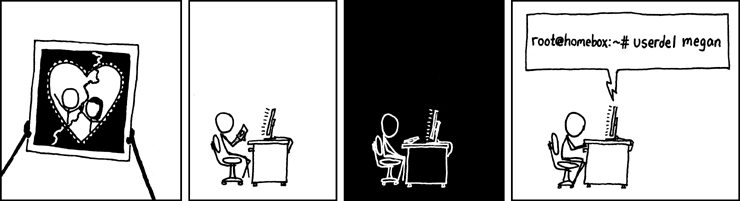

Image Source: XKCD

Introduction

In computing, permissions define the level of access, privilege, and control that users have over files, applications, and other system resources. These permissions are divided into three broad categories: Read (R): letting users view the content of files and directories, Write (W): letting users create, modify, and delete files and directories, and Execute (X): letting users run files or programs.

Unauthorized access to system resources, especially by malicious actors, can lead to dire consequences. Therefore, it is important to set and manage permissions appropriately. In this post, I’ll share briefly about how to manage permissions in Linux.

Users and Groups

To begin, we must first understand the concept of users and groups in Linux. A user is an entity that can log in and interact with the system, typically representing a person or a service. Each user has a unique username for friendly identification, a unique numerical identifier (User ID - UID) for the system to identify the user, and a home directory (usually in the form /home/username) to store user-specific files.

A user can be:

- The

Root UserorSuperuser, with unrestricted access to all commands and files on the system, allowing them to perform any actions and system-level tasks. - A regular user, with limited permissions and restrictions to their own files and certain system resources.

- A

System User, associated with system services and applications used to run background processes to keep the system functioning.

Each user’s information, including their username, UID, home directory, and shell, is stored in the /etc/passwd file, while passwords are typically stored in a hashed format in the /etc/shadow file.

Groups, on the other hand, represent collections of users that can be managed as a single unit. They are used to manage user permissions and access control for files, directories, and system resources. Each group has a Group ID (GID) and is defined in the /etc/group file, which lists group names, GIDs, and the users who are members of the group.

Each user is assigned to a primary group. The Primary Group is specified in the user’s account information and determines the group assigned to files created by the user. Each user must belong to one primary group. Secondary Groups specify one or more groups to which a user can belong, granting additional permissions and access to resources shared among users in the group. Typically, a Linux user can belong to up to 15 secondary groups.

Users and groups together are used by the system to define and enforce access and permissions.

Permissions

As mentioned earlier, each file and directory in a Linux system has three types of permissions: r (read), w (write), and x (execute). These permissions are defined for three types of entities: the file/directory owner (user), the group, and others (everyone else in the system). Permissions are represented as a 10-character string, such as -rwxr-xr--.

The first character indicates the file type (- for a regular file, d for a directory, and l for a symbolic link), and the remaining nine characters represent the permissions for the owner, group, and others in sets of three:

- The first set of three characters (e.g.,

rwx) represents the owner’s (user’s) permissions. - The second set (e.g.,

r-x) represents the group’s permissions. - The third set (e.g.,

r--) represents the permissions for others.

A - means there are no permissions for the corresponding operation. For instance, r-x means read and execute permissions are granted, but not write permissions.

You can view permissions on a Linux machine using the ls -l command:

$ ls -l

-rw-r--r-- 1 user group 4096 Jun 29 01:49 foo.txt

In the example output above, -rw-r--r-- represents the permissions, user is the username of the owner, and group is the group name for the corresponding group.

Modifying Ownership and Permissions

You can change the ownership and group of a file using the following commands:

chown user file: Changes the owner of a file.chgrp group file: Changes the group of a file.chown user:group file: Changes the owner and group of the file.

Typically, the chgrp command can be used without sudo if the user is changing to a group they belong to, while chown almost always requires sudo (superuser do) for changing the ownership of a file.

Permissions can be changed using the chmod command in two main formats:

- Symbolic Mode: Using letters to specify and modify permissions. For instance:

chmod u+w file: Adds write permissions for the user (owner) of the file.chmod g-x file: Removes execute permissions from the group on the file.chmod o=r file: Sets read-only permission for others on the file.chmod a+rw file: Adds read and write permissions for all (user, group, others) on the file.

- Numerical (Octal) Mode: Uses numbers to specify permissions.

- Each permission type is represented by a number: read (

r) is 4, write (w) is 2, and execute (x) is 1. - Permissions are summed up for each entity. For example,

rwx(read, write, and execute) is 4+2+1 = 7. chmod 755 file: Sets permissions torwxr-xr-x(7 for user, 5 for group, 5 for others).

- Each permission type is represented by a number: read (

Special Permissions

There are a few special permissions in Linux:

-

Setuid (set user ID): When set on an executable file, it allows the file to be executed with the permissions of the file’s owner. It is represented by an

sin the owner’s execute position (e.g.,rwsr-xr-x). It can be modified usingchmod, as inchmod u+s fileor by adding a4at the start of a permission set when using numerical mode withchmod, e.g.,chmod 4755 file. -

Setgid (set group ID): Similar to Setuid, it allows a file to be executed with the permissions of the group it belongs to (e.g.,

-rwxr-sr-x). It can be modified usingchmod g+s fileor by adding a2to the start of the permission set when using numerical mode, e.g.,chmod 2755 file. -

Sticky Bit: When set on a directory, it ensures that only the owner of the directory (or root) can delete or modify a file in the directory. It is represented as a

tin theexecuteposition of theothers'permission set (e.g.,drwxrwxrwt). It can be modified usingchmod +t directoryor by adding a1to the start of the permission set when using numerical mode, e.g.,chmod 1755 directory. It only applies to directories.

Learn More

To learn more about Linux and Linux Permissions, you can explore these resources:

- RedHat: Linux Permissions Explained

- RedHat: Managing User and Groups in Linux

- ArchLinux: Users and groups

And you can always consult the Linux Manual Pages.

Cheers.