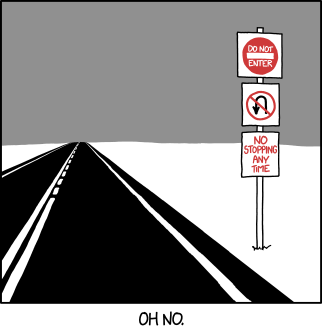

Traffic Jams

Image Source: XKCD

Accompanying Spotify Playlist (because “Traffic Jams”)

“Why, why? But why is this happening?” This was my exact thought when I landed at the Seattle airport on a seemingly ordinary Wednesday afternoon. My maps app lit up with bright red and yellow lines, showing the major highways into the city—I-5, I-190, SR 520—choked with traffic. I wasn’t thrilled, to say the least. I knew I could take alternate routes like Highway 99 or 509, but that didn’t quell my burning curiosity. It also didn’t help that on my flight over; I read a Komo News report about how INRIX, the location and traffic data analytics company, found that the average Seattle driver lost 58 hours in traffic jams in 2023, making the city home to the 27th-worst traffic in the world (you can read about the findings and methods here). So why was there so much traffic? It couldn’t be a car crash; what were the odds of massive pile-ups on three highways on a sunny Wednesday afternoon? Road work didn’t seem likely either, as that typically happens at night or on weekends. And it wasn’t rush hour. So, what was causing the gridlock? I wanted to find out.

Typically, traffic jams occur when sections of the roadway are blocked off, or obstructions on the road require drivers to use alternate routes. For instance, when there is a car accident, traffic might be rerouted, or when there is construction work, cars are diverted to different routes. Other instances include inclement weather, requiring drivers to proceed cautiously; rush hour, where there is a sudden and massive increase in the number of cars on the road; or saturation, which in traffic engineering means the number of vehicles on the road has exceeded its capacity, causing a jam to build up. However, while these are reasonable explanations for traffic jams, they don’t quite explain instances where there is a traffic jam with no apparent cause. Or cases where a jam builds up and dissipates without a clear reason for its start or end. This brings us to the concept of phantom traffic.

To introduce phantom traffic, I will start by sharing a recent conversation with my skip manager at work. He talked about participating in STP, a 200+ mile bike ride from Seattle to Portland. This multi-day cycling event draws thousands of riders willing to brave the challenge. You can learn more about STP here. Now, back to my skip manager. Because this is a long event, conserving energy and using all available advantages is crucial. Participants take advantage of the draft effect, where a rider in front forces through the air, creating a wake or slipstream that allows riders behind to move at the same speed with much less effort. However, this process is complicated, as my skip manager highlighted.

If a rider in front needs to brake, simply braking would endanger the riders behind, following closely at the same speed. Sudden braking can take them by surprise, cause an immediate crash, or cause them to react suddenly in a manner that endangers their and other’s safety. To avoid this, the rider in front communicates the need to brake to the person behind, who then passes the message down the line. This ensures that everyone is prepared, and the rider in front can brake while each rider behind reacts accordingly without running into anyone. For this system to work, all riders must be in sync, moving and slowing down or speeding up at the same rate.

We see a similar effect when driving on a highway with several cars moving at roughly the same speed. If all drivers maintain their speed and roughly the same spacing from each other, traffic flows steadily. But say one driver abruptly slows down (even if just slightly); each driver behind notices and reacts, but they brake a little more strongly as they were not fully prepared for the event. This creates a chain reaction, with a wave of slowing vehicles propagating through the roadway. Vehicles slow down to avoid a collision, and when situations are safe, they accelerate back up to normal speed. This causes a traffic jam, and vehicles enter the jam faster than vehicles can accelerate out of it; hence, the jam continues until the rate at which vehicles enter the jam becomes low enough for the vehicles leaving the jam to restore normal flow. And as human behavior is imperfect, these traffic jams will continue as we utilize our roadways.

Typically, this effect is not observed on roads where the density of cars is low. In those cases, cars can quickly adjust to abrupt changes in speed and maintain a smooth traffic flow. However, as the number of cars increases to a critical mass, we start to see this effect and the corresponding stop-and-go traffic jams.

To model this effect, I took inspiration from the work done by researchers and people who have studied traffic, and I built a phantom traffic simulator to accompany the blog post. You can find it in this Github Repository. You can fork the repo and play around with the simulator, tweaking it, perhaps to see how things change when you increase the number of vehicles, modify how the speed changes, etc. I have tried to keep it lightweight, but if you can improve it and make it more robust, I would love to see your work. :)

You can also find other great traffic simulators here or see how traffic flows through different types of junctions this video.

Beyond increasing the time it takes for road users to get to their destinations, phantom traffic is also very inefficient for vehicles because when cars are decelerating or coasting, they burn less fuel and emit much less toxic gases. But when cars drive and stop, and then drive and stop in areas with phantom traffic, each accelerating run burns more gas and emits more pollutants. Research has also shown that phantom traffic causes more accidents as drivers could overreact or underreact to what might happen in front of them (think back on the biking example from STP). Optimistically, autonomous vehicles driving on the roadway dynamically adjust their average speed with knowledge of the traffic ahead, which could help reduce phantom jams. Likewise, such driverless vehicles can be modeled to compute the best following distance and speeds to prevent traffic buildup or react in ways that reduce them.

In conclusion, traffic that seemingly comes out of nowhere is caused by humans being imperfect, and our actions on the road affect other drivers, which can lead to the buildup of jams. Or, as put more bluntly in this Freakonomics article: What Causes Traffic Jams? You. With this knowledge, we can be more forgiving and calm when traffic seems to appear out of nowhere, and more conscious of how our driving (say slowing down slightly to go back 30 seconds on a podcast), can affect other drivers and the flow of traffic on the road.

As a side note, I’ve also been reading a little about why increasing the size of the road does not solve problems with traffic jams. Here are some great articles to learn more about it: What’s Up With That: Building Bigger Roads Actually Makes Traffic Worse, Question Your World: How Does Roadway Expansion Cause More Traffic?, as well as a video.

References

And resources to learn more from:

- Why the @#$% is there so much traffic? - Benjamin Seibold

- Shockwave traffic jam recreated for first time

- Traffic Waves

- Traffic Jams

- A Mathematical Introduction to Traffic Flow Theory

- Traffic Modeling - Phantom Traffic Jams and Traveling Jamitons