URL (or Percent) Encoding

Why URLs Speak in Code

Image Source: XKCD

Introduction

Have you ever clicked on a link or typed a web address only to see something strange in the URL? Maybe it looked like this:

https://internet.com/explore/search?query=what+is+a+good+application+of+N%C3%A4ive+Bayes+in+deep+learning

when your search query was: what is a good application of Näive Bayes in deep learning. Or perhaps you encountered something like this:

https://internet.com/travel/hotels/courtyard%20by%20marriot%20D%C3%BCsseldorf

when you were looking for Marriot hotels in Düsseldorf, Germany.

What are all those % signs and numbers? Are they some kind of secret code? In this blog post, we’re going to unravel the mystery behind these symbols and take a deep dive into URL encoding, ASCII, and the fascinating story of URLs themselves.

What are URLs?

A URL (Uniform Resource Locator) is the cornerstone of how we navigate the web. Simply put, a URL is an address that tells your browser where to find a specific resource, such as a webpage, an image, or a file. You can think of it as a digital version of a friend’s home address—it ensures that when you need something from your friend, you know precisely where to go to receive the article reliably.

A typical URL would look something like this:

https://www.internet.com:8080/path/to/resource?query=parameter#fragment

Here’s the breakdown:

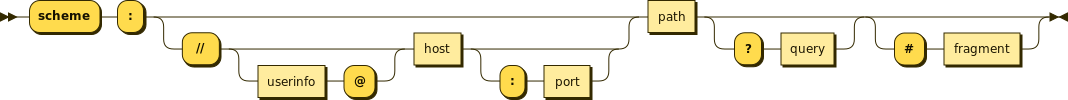

Image Source: Wikipedia

- Protocol/URI Scheme(

https://): Specifies how your browser should communicate with the internet server. Common protocols includehttp/https(securehttp),ftp(file transfer),mailto(email address) and more. While network protocols are not the focus of this blog post, you can learn more about them in these articles: Types of Network Protocols and Their Uses, What is a network protocol?, Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) Schemes - Domain(

www.internet.com): Identifies the server hosting the internet resource. This is typically a human-readable name that maps to an IP address via DNS (Domain Name System). For a given domain, you can easily look up the corresponding IP address in DNS. For instance, on my local machine, I can use thehostcommand or thenslookuputility to take a look at the IP addresses for Google servers. Public tools like DNS Checker and MX Toolbox are also handy for peeking at DNS records for domains. - Port(

:8080): Optional and specifies which port the server should use. The default forhttpis 80, and forhttpsit’s 443. Other port numbers and the corresponding protocols are21forftp, and22forssh, etc. The port essentially specifies which application or service on a server to connect to via the URL. If the URL is your friend’s home address, the port number can be thought of as your friend’s room. - Path(

/path/to/resource): Indicates the specific location of the resource on the server. It’s like the folders and files on your computer. - Query(

?query=parameter): A set of key-value pairs used to pass information to the server. For example, a search query when we want to learn about Näive Bayes or a user’s preferences when making a request from the server. - Fragment(

#fragment): Refers to a specific section within the resource. For instance, it could be specific lines in a text file, a particular section or a bookmark on a webpage.

Where Did URLs Come From?

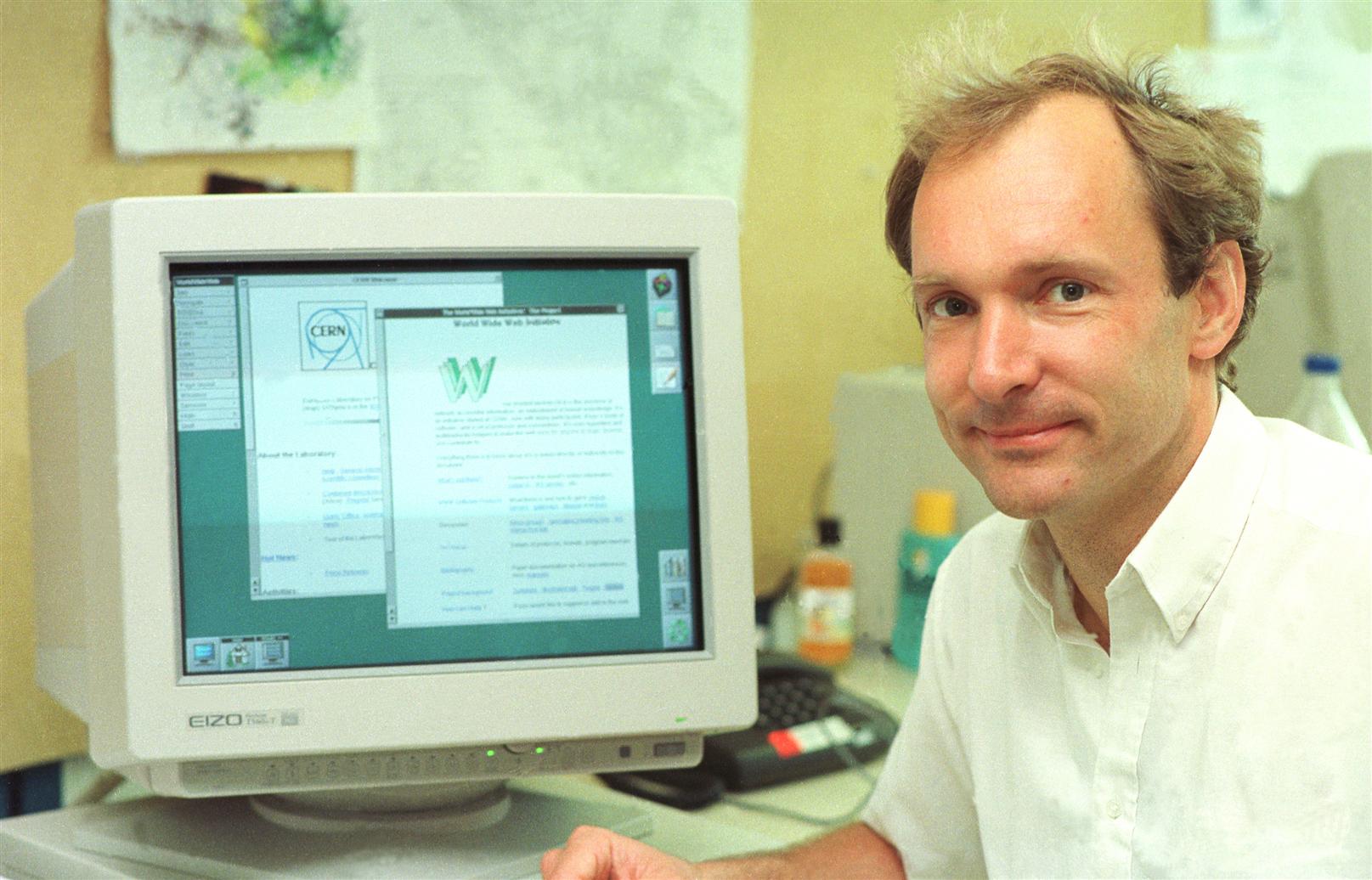

Image Source: CERN

In 1992, Tim Berners-Lee introduced the concept of URLs alongside the HTTP protocol and HTML as a way for researchers to share and access documents easily.

Berners-Lee has already proposed the ideas of the World Wide Web. However, for this network to function, it needed a standardized way to identify and locate resources. To address this need, he proposed the idea of the URL to serve as a “document identifier.” The URL became one of the three core components of the web, alongside HTML (for structuring documents) and HTTP (for transferring them).

Initially, URLs were simple and primarily used to point to static files hosted on servers. Over time, they evolved alongside the web into a versatile system supporting dynamic content, user input, and even encrypted communication. Throughout this evolution, the central principle of universality—the idea that URLs should work on any device and in any context—has stood the test of time.

ASCII and Its Role in URL Encoding

To understand the “strange” encodings we see in URLs, we need to look back at the history of ASCII. The American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) was developed in the 1960s as a standardized way for computers to represent text characters. Before ASCII, there were numerous incompatible encoding systems, which made it challenging for different systems to communicate. ASCII changed that by providing a universal 7-bit character set, which could represent 128 unique characters.

This 128-character set included:

- Printable characters: Uppercase (

A-Z), lowercase (a-z), digits (0-9), and symbols like@,#, and$, etc. - Control characters: Instructions for managing text streams, such as newline (

\n) and tab (\t).

ASCII’s simplicity and universality made it the foundation for early computer systems and networks, including the internet. However, its biggest limitation was its inability to represent non-English characters, like é, ß, or 中, as well as other writing systems like Cyrillic, Arabic, and Chinese. The biggest reason for this limitation is because, at the time it was invented, memory and processing power were incredibly expensive; hence, every bit mattered. By sticking to 7-bits, and, thus, 128 characters, ASCII struck a balance between functionality and efficiency. It was small enough to fit into the limited storage and memory of the time yet comprehensive enough to provide a range of characters to work with. Likewise, it was a light-weight, simple, easy-to-implement solution and universal (at least for English-speaking developers).

Expanded Character Sets (Beyond ASCII)

Image Source: XKCD

As the internet connected the world, the need for a broader character set became apparent. This led to the development of Unicode, which could represent virtually every character in every language. Unicode works with multiple encodings, such as UTF-8, UTF-16, and UTF-32 (You can read more about them here: Difference between UTF-8, UTF-16 and UTF-32 Character Encoding? Example)

UTF-8 is the most widely used encoding on the web today. It is backwards-compatible with ASCII, meaning that all ASCII characters retain their original binary values, while non-ASCII characters are represented using additional bytes. For example:

- The ASCII character

Aremains01000001in binary under UTF-8. - The Unicode character

éis represented as11000011 10101001in UTF-8.

Despite Unicode’s dominance in modern text representation, URLs remain constrained to ASCII due to backward compatibility and simplicity. Early internet protocols, including URLs, were built on ASCII. Changing this foundation would disrupt countless systems and applications.

To address this, the solution was percent-encoding, or URL encoding, which allows characters outside the ASCII range to be safely represented in URLs.

URL Encoding

URL encoding ensures that any character—whether it’s unsafe, reserved, or non-ASCII—can be safely transmitted in a URL. Here’s how it works:

- Identify Characters to Encode:

- Reserved Characters: Characters with special meanings in URLs (e.g.,

?to start a query string,&to separate parameters,/to separate path components, etc.) must be encoded when used outside their context. - Unsafe Characters: Characters like

spaces,<,>,{,}, etc., are unsafe because gateways and transport agents might modify them. Encoding prevents such misinterpretation. - Non-ASCII Characters: These characters, which fall outside the ASCII set, must be encoded for compatibility across systems.

- Reserved Characters: Characters with special meanings in URLs (e.g.,

- Convert Characters to Hexadecimal ASCII:

- Each character is replaced with a

%followed by its two-digit hexadecimal value. (Use this handy URL Encoding Reference) mapping characters to their hexadecimal values.

- Each character is replaced with a

Details Examples of URL Encoding

Reserved/Unsafe Characters in Query Strings

Original: https://internet.com/search?q=C++&C Programming

Encoded: https://internet.com/search?q=C%2B%2B%26C%20Programming

Here,

+becomes%2B(reserved character).&becomes%26(reserved character).Space(%20(unsafe character).

Non-ASCII Characters

Original: https://internet.com/profile?name=Günter Hernández François

Encoded: https://internt.com/profile?name=G%C3%BCnter%20Hern%C3%A1ndez%20Fran%C3%A7ois

In this case,

üis encoded as%C3%BC.áis encoded as%C3%A1.çis encoded as%C3%A7.Spaceis encoded as%20.

Below are examples of encodings for some reserved characters:

| Character | ASCII Value | Encoded Value |

|---|---|---|

, |

44 (0x2C) |

%2C |

/ |

47 (0x2F) |

%2F |

: |

58 (0x3A) |

%3A |

; |

59 (0x3B) |

%3B |

= |

61 (0x3D) |

%3D |

? |

63 (0x3F) |

%3F |

@ |

64 (0x40) |

%40 |

[ |

91 (0x5B) |

%5B |

] |

93 (0x5D) |

%5D |

And correspondingly, for some non-ASCII Unicode characters:

| Character | Description | Unicode Code Point | UTF-8 Encoding | URL Encoded Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

ç |

Latin small c with cedilla | U+00E7 |

C3 A7 |

%C3%A7 |

é |

Latin small e with acute | U+00E9 |

C3 A9 |

%C3%A9 |

ß |

German Eszett (sharp S) | U+00DF |

C3 9F |

%C3%9F |

中 |

Chinese character | U+4E2D |

E4 B8 AD |

%E4%B8%AD |

π |

Greek small letter pi | U+03C0 |

CF 80 |

%CF%80 |

🎉 |

Party popper emoji | U+1F389 |

F0 9F 8E 89 |

%F0%9F%8E%89 |

🚀 |

Rocket emoji | U+1F680 |

F0 9F 9A 80 |

%F0%9F%9A%80 |

Conclusion

URL encoding is a critical mechanism that allows URLs to safely transmit a wide range of data while maintaining compatibility with the internet’s ASCII-based foundation. So, the next time you see %20 or %C3%A9 in a URL, don’t panic—it’s just the internet’s way of speaking a language that devices all around the globe can understand.

References

While I have cited a handful of sources in this blog post, below are some other resources that I used to write it and that can be useful for your further learning.

- HTML URL Encoding Reference

- HTML ASCII Reference

- Punycode: A Bootstring encoding of Unicode for Internationalized Domain Names in Applications (IDNA)

- What Happens When You Enter a URL In Your Browser of Choice

- The birth of the Web

- Uniform Resource Identifier (URI): Generic Syntax

- URL Encoding and what characters are valid in a URI

- The Blessing of Unicode

- Reserved and excluded characters

- Types of Network Protocols and Their Uses

- What is a network protocol?

- What is a URL (Uniform Resource Locator)?

- The components of a URL

- Uniform Resource Identifier (URI) Schemes

- How domain name is transferred in IP address?

- Difference Between Domain Name and URL

- What is the difference between a website, domain name and a URL?

- port number

- What Are Ports?

- Difference Between IP Address and Port Number

- Query Parameters and URI Fragments in URLs

- The History of the URL

- Document identifiers

- Computer Mail Meeting Notes

- How The URL Was Built

- Information Management: A Proposal

- Timeline of ASCII History

- Unicode: The Journey From Standardizing Texts to Emojis